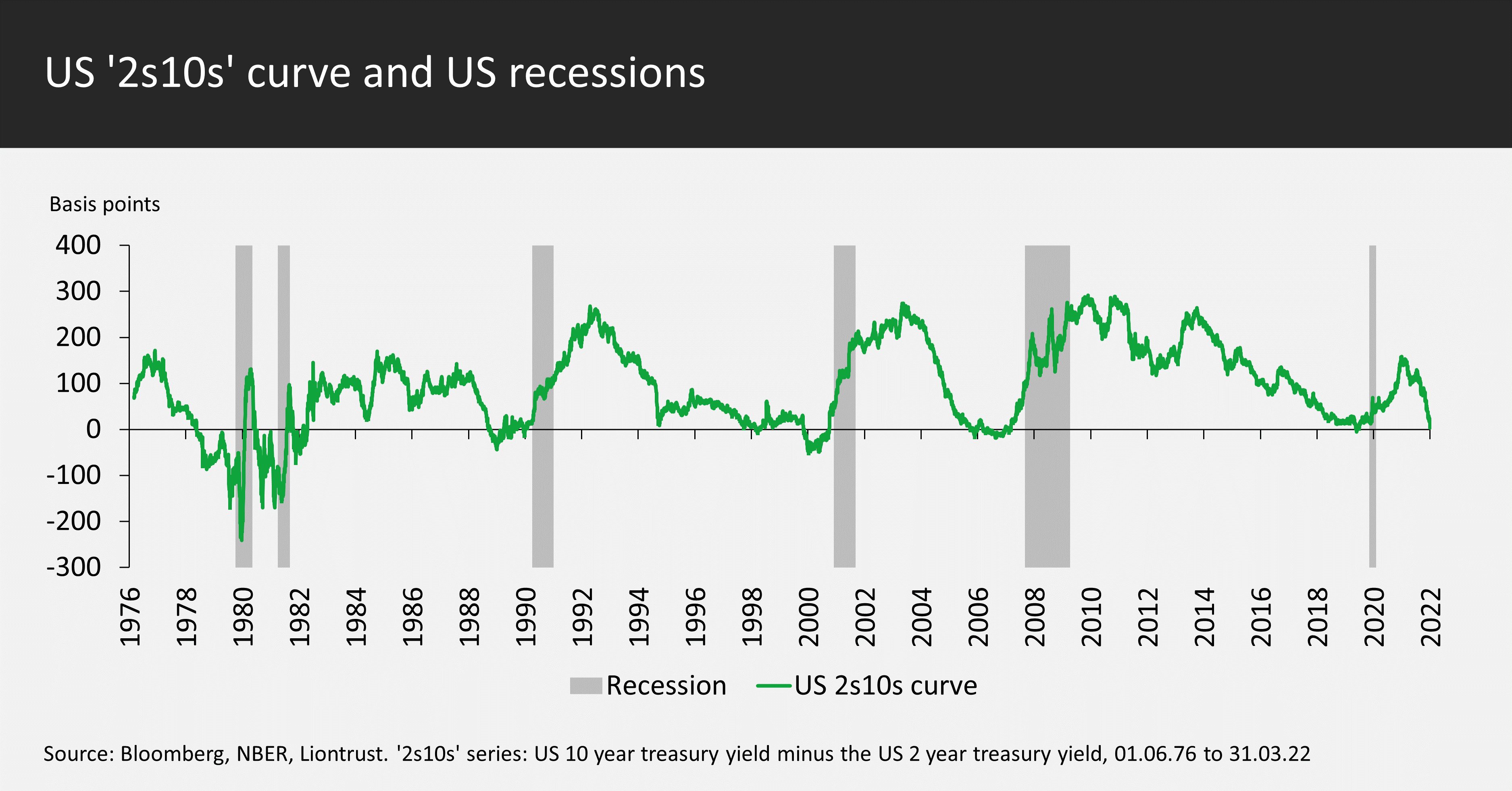

Every US recession in the last 50 years has been preceded by an inversion of the US yield curve. This much-followed market indicator has infamously predicted nine of the last six recessions, but even with the false positives it is a phenomenon that cannot be ignored. In March, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates for the first time since 2018; by the end of the month, the curve had briefly inverted intra-day. It was back in an inverted position at the start of this week.

I should note that others prefer to look at 3-month yields compared to the 10-year. The two generate similar results but the 2s10s is more forward looking. On average, it takes about 18 months after the 2s10s yield curve inverts before a recession starts, but there is a large variation around the timing. There is less of a lag between any inversion of the 3-month versus 10-year yield differential and a recession occurring – this just shows that policy had become too tight (interest rates are too high and have choked off growth and investment). Presently, the curve between 3 months and 2 years in the US is very steep; effectively telling you that the Federal Reserve is hugely behind in this cycle and will be increasing interest rates rapidly to try to catch up.

The Fed has its own preferred measure (the 18-months forward 3-month rate minus the current 3-month rate), but all it currently shows is that the Fed should not have left policy so loose for so long – we have been vocal in that regard since early 2020. More interestingly, officials were keen to talk about the prospect for an economic soft landing, such as that achieved in 1994. The bond market clearly disagrees, as you can see from the narrowing of the spread between 10-year and 2-year yields in the chart above (a flattening of the yield curve), before the yield curve’s inversion. So, is it “different this time?”

There is an argument that quantitative easing (QE) has depressed the term premium, the extra yield one should be paid for owning longer maturity government bonds. I have some sympathy with this but would counter that QE has also kept short rates too low. Whilst the yield curve would probably be steeper without QE, the flattening of the last 3 months cannot be ignored. This is particularly the case as we rapidly approach the period when quantitative tightening (QT) will start.

Although interest rates were much higher half a century ago, there is strong similarity with the experience in the 1970s in that the curve currently is inverting as we witness a supply shock. Firstly, the pandemic constrained supply and, post the great economic reopening, there are still bottlenecks throughout the supply chain including, for example, for semiconductors. Now Putin’s war has caused further spikes in commodity prices. These will continue to feed into headline inflation over the months to come. But will they feed into core inflation in the longer term? For this we need to look at the demand side of the equation.

The consumer is in a fortunate position of having a strong balance sheet, with excess savings having accrued during the pandemic lockdown periods. These savings are not distributed equally, with socio-economic groupings A to C owning the vast majority. Thus, it is the lower socio-economic groups that not only lack savings but also have a higher exposure to headline inflation through the necessity of heating and eating; such basics are frequently excluded from core inflation calculations. The wallet substitution impact of higher energy prices can be mitigated in two ways, government intervention (with huge variance country by country) or by wage inflation. Labour markets are tight and elevated wage inflation remains our central case for the next couple of years – hence why central bankers are having to act.

For some time, we have believed that economies are comfortably strong enough to live with interest rates being higher for longer, especially if they curb inflation and actually improve living standards. This is on the basis that, for example, the Federal Reserve raises rates to the 2% area and keeps them there, rather than raise more aggressively only to cut in short order. With some Fed voting members now wanting rates above 3% the goalposts have shifted and there is a real danger rates are now raised to recession-inducing levels.

So, to answer whether it will be different this time: if the Fed rapidly raises interest rates to be above 3%, then we think a recession is likely to follow in 12-24 months’ time (so, no, it is not different this time); if, however the Fed is partly just talking a hawkish game to discourage inflation expectations and pauses at 2%, then we will expect a soft landing and the yield curve to start steepening again.

Key Risks