“…central banks cannot grow more food, supply more gas or make the wind blow stronger.” - The Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee’s Professor Jonathan Haskel

Executive summary

At the time of writing, global stock markets are experiencing significant dislocation. The ‘risk-off’ mood has had many sources: the prospect of a rapid tightening of central bank policy to head off inflation, a more challenging earnings outlook, in part due to supply disruptions and inflationary pressures, and mounting tensions between Russia and the West and the worrying prospect of conflict in Ukraine.

Our portfolios have not been immune to these ructions, which have been driven by sentiment and factor rotations rather than fundamentals. Equity markets are forward looking, and short-term traders are by nature the fastest to react, selling down growth in favour of value, high P/E in favour of low P/E, small- and mid-caps in favour of the perceived safety of large-caps.

We have been active throughout this period and embarked on moderate tactical rebalancing of the portfolios last year which has continued in January. This has been done within the framework of our long-term, fundamental approach, where we have predominantly reallocated capital to existing holdings in well-managed businesses that are operationally robust and exhibit Darwinian characteristics – businesses that are able to seize the opportunities presented by uncertainty. Moreover, although the market activity has largely been sentiment driven, we have increased our engagement with management teams and have been rechecking our own assumptions and investment theses. Ultimately the key determinant of performance for the Fund will be business plan delivery from each of the companies we own. As we wrote in our recent quarterly fund reports, we have been impressed with the operational pulse of our holdings in what has been a challenging environment, and remain confident about their ability to generate attractive returns over the longer term.

With inflation the pressing topic of the moment, we devote the rest of this newsletter to “greenflation” and the way ESG and the energy transition are reshaping long-term global supply and demand dynamics.

The future of inflation has a green hue

“Greenflation” is a recently coined term that has gained currency in the last quarter to denote the surprisingly powerful and potentially persistent knock-on effect of ESG in its widest societal sense, and especially of one of its key tenets, the energy transition. While we embrace our role in helping to create a more sustainable economy, we have been surprised by the level of inflationary risk associated with ESG that has emerged in a relatively short period of time. Greenflation, therefore, warrants careful attention and is an issue we are considering as a team in terms of the risks and opportunities it presents to our holdings, as well as its implications for the wider macro backdrop.

Each of the “ESG” constituents has the potential to be inflationary, at least in the short to medium term, in many cases due to temporal mismatches between the desire and ability to transition quickly. We will touch on the inflationary cost in relation to “E” in a moment. Examples of the “S” might include increased aggregate wage costs associated with closing the gender pay gap, increasing workplace diversity and ensuring fair pay and conditions for supply chains. Meanwhile, under “G” the costs associated with increased reporting and oversight have potentially inflationary consequences. Some of these additional costs will lead to an initial price adjustment, which may be inflationary in the short term but not over a longer period.

The price of the energy transition

When it comes to environmental issues, the spike in energy and commodity prices has in part been a consequence of the pace at which investors are now demanding change. The oil and gas sector improved its capital discipline during the last decade, rightly cutting investment in more marginal projects. This lower level of investment, combined with heightened awareness of the climate emergency which has spurred demand in the funds industry (and wider society) for robust decarbonisation plans, has meant that increased demand for hydrocarbons is less likely to result in increased investment in supply, at least for listed oil & gas businesses. This has even been true in the US shale sector despite being highly levered to a rising gas price; higher capital costs have played a part with investors shunning this sector.

In the EU, rising gas prices have been due to a combination of supply uncertainties, in part due to deepening tensions with Russia, the ongoing retirement of nuclear power in Germany, and a lack of wind to drive wind turbines. Debate about whether to include nuclear and gas in the EU’s sustainability taxonomy speak to the powerful divisions about the most effective path towards a low carbon economy. Ultimately, what is included and excluded in an investment mandate, or indeed a country’s energy mix, will have a material influence on the availability and potential cost of capital, with a potential impact on the orderliness of the transition to a low carbon economy.

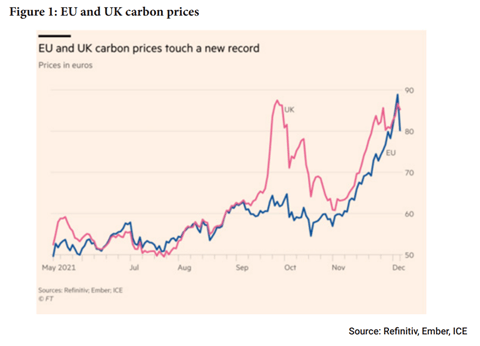

Germany’s decision to end nuclear power, for example, is certainly contributing to the current energy crisis and has increased reliance on Russian gas, creating potentially dangerous geopolitical leverage which has been playing out in January on the eastern border of Ukraine. Environmentally, the shortage of gas in the EU has led to a surge in the use of coal and has contributed to the spike in the price of carbon permits [Figure 1]. One knock on effect of the sharp rise in the cost of carbon on the European and UK emissions trading markets is that it makes some greener energy sources more viable, such as green hydrogen. A sustained period of higher prices could indeed accelerate the development and adoption of this technology, which would be deflationary over the long term. This is an example of higher energy prices having a green lining.

Funding the transition

The decision of many institutional investors to shun large parts of the energy sector does potentially pose risks in terms of the how smooth or disruptive the transition will be, which is likely to be borne out in economic disruption such as inflationary spikes in the cost of energy. In a recent Financial Times op-ed, Morgan Stanley’s Ruchir Sharma referred to feedback from a broker who reported that only one of the firm’s 400 institutional clients was willing to invest in fossil fuel businesses. Banks are under pressure to follow suit. Although we are fully behind the need to transition to a green economy – and at pace – we believe divestment is a fairly blunt tool as it simply doesn’t acknowledge a) the role fund managers can play in overseeing the transition, applying checks and balances through engagement with investee companies, b) the role of some fossil fuels in effecting this transition and c) that assets are often sold to private investors who are not held to the same climate goals as public companies. Going green will take vast amounts of energy. The phase out of unfettered coal is urgent. However, despite the obvious lock-in risk associated with prolonging the global dependence on fossil fuels, transition fuels like natural gas are vital to allowing low-carbon energy sources and technologies (and their associated infrastructure) to achieve scale.

Mining for EVs

And, indeed, the dash to achieve scale has led to inflation across the commodity complex. The price of copper, which is an essential ingredient in electric cars and renewable energy, has more than doubled from its lows in 2020, and the price of aluminium has also risen sharply. The energy transition won’t happen without minerals and metals. Solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, nuclear, electric cars: they all variously rely on copper, aluminium, cobalt and lithium. The following quote from “Mining our green future”, an article written by Profession Richard Harrison and published in Nature, puts the supply and demand imbalance into sharp relief:

“To switch the UK’s fleet of 31.5 million internal combustion energy vehicles (ICEVs) to battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) would take an estimated 207,900 tonnes cobalt, 264,600 tonnes lithium carbonate, 7,200 tonnes neodymium and dysprosium and 2,362,500 tonnes copper. This is twice the current annual world production of cobalt, an entire year’s world production of neodymium and three quarters of the world production of lithium. To do the same worldwide would need forty times these amounts.”[i]

Despite the best will in the world to create a fully circular economy where metals are recycled and reused, the expected pace of the energy transition means the lion’s share of demand in the short term is likely to be met from mined raw materials, with these materials continuing to plug a large shortfall for decades to come. Currently only 1% of lithium demand is met by recycling. This figure is closer to 30% for metals such as aluminium and cobalt, despite end-of-life recycling rates of nearer to 70%.[ii] A reasonably circular economy for car batteries could be achieved in the US by 2035 if penetration of electric vehicles hits 245 million and assuming an annualised scrappage rate of roughly 6.9% or 17 million vehicles, although that would imply a much higher recycle rate than currently exists or is expected. The message is clear: raw materials will remain in the mix for some time yet and fund managers will have a role in ensuring that mines and supply chains adhere to recognised international standards in terms of safety, employment and human rights.

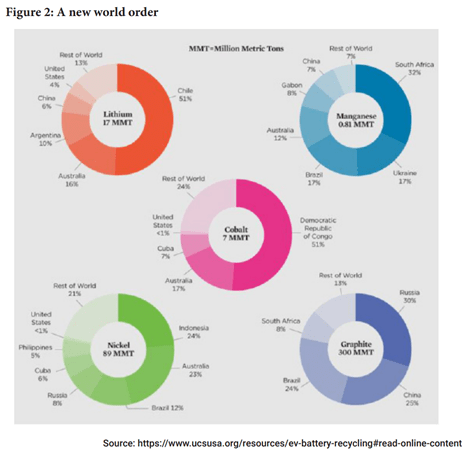

The electrification of transport has started to shift the world order in terms of key resource suppliers, with over half of the world’s lithium and cobalt coming from Chile and Democratic Republic of Congo, respectively [Figure 2]. Both countries have supply challenges and reports of child labour in DRC have been particularly troubling. Human rights abuses are not a trade-off for the energy transition, and we carefully monitor the societal impacts of the mining exposure we hold and engage firmly on these issues.

Longer-term, there is scope to source a reasonably significant amount of cobalt from European nickel mines, while the deep ocean might also provide another source, a controversial option with associated environmental risks. Moreover, technological advances should continue to improve battery efficacy and broaden the scope for substitutes (e.g., hydrogen). Nevertheless, the move to electric mobility is expected to cause a fivefold increase in demand for lithium and cobalt which suggests persistent price pressure for these increasingly vital metals.

Changing supply chains to beat climate change

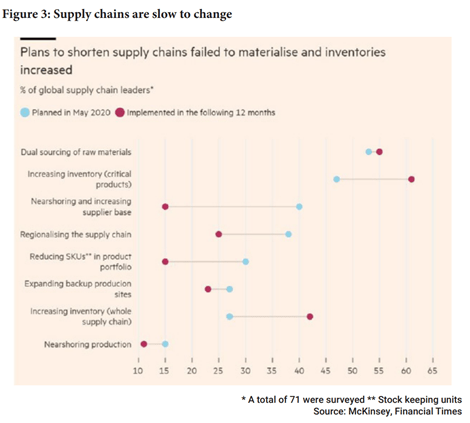

Both Covid and heightened awareness of the climate emergency have torn up the rule book for global just-in-time supply chains, with long-term inflationary consequences. The vulnerabilities of the just-in-time model, which sought to optimise working capital and keep inventories down, have been resoundingly exposed by the global pandemic. Over time, climate-related risks are likely to have a similar impact. Nevertheless, a move to a just-in-case model with a greater focus on resilience is likely to increase working capital costs in part due to higher wages, which will pressure margins or increase prices for customers or a combination of the two.

The world is going to a new normal involving higher inventory levels and shorter supply chains, with manufacturing sites closer to the point of sale. As Figure 3 suggests, this process is likely to be lengthy and could have inflationary consequences for some time yet. However, these pressures should ultimately be balanced by lower shipping costs, better management through tools such as AI and coordination between competitors, reduced disruption risk and lower carbon emissions. Nevertheless, some of the world’s largest businesses are already making inroads, and this process is occurring at holdings such as Fever-Tree, with the business building domestic operations in the US to support its growth plans.

Technology’s deflationary role

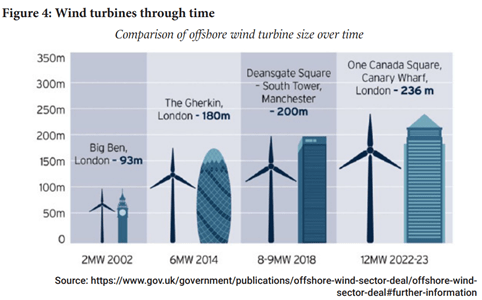

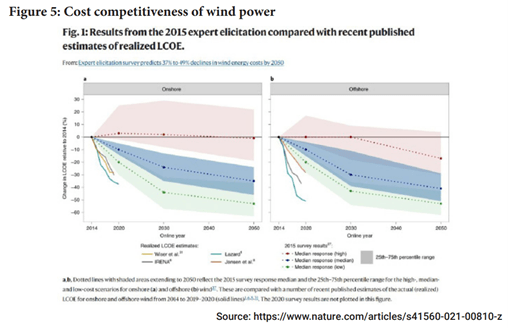

There is little doubt that advances in technology that improve productivity and operational efficiency are deflationary – any textbook on microeconomics will attest to the fact. One of the exciting aspects of the energy transition is the fact it can and has the potential to bring down the lifecycle, also known as the “levelised”, cost of energy. Indeed, costs of wind and solar power fell rapidly and became cost competitive with fossil fuel technologies in the early 2010s. A simple, visually striking demonstration of the technological improvements in the area of renewable energy is the significant increase in the size and power output of wind turbines, as shown in Figure 4.

AI in supply chains, autonomous vehicles, robotics in healthcare – there are many big gains to be made which will mean technology will continue to be a formidable deflationary force. When it comes to energy, there is growing excitement about the prospect that marginal costs will eventually fall to zero through the mass rollout of existing and new technologies. This would indeed be a gamechanger for the global economy. However, while prices are continuing to fall in conventional renewable technologies (see Figure 5), we are not there yet. Some technologies are easier to implement than others – larger wind turbines are low hanging fruit, for example. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) has been much harder to implement, in part due to expense, as well as general logistics – it is an inflationary technology which reduces the cost competitiveness of fossil fuels. Mini-nuclear reactors have great potential to bring rapid change to the energy mix at a relatively lower cost than larger nuclear plants, although nuclear is unpopular in Germany and among many environmental activists. Nuclear fusion, which represents the holy grail in terms of reliable zeroemission, zero-waste energy, has captured recent headlines following encouraging laboratory tests. The UK Government has also backed research into this area in the hope of bringing reactors online by 2040. Yet many experts in the field believe it is unlikely to reach commercial scale before about 2050[iii], which is too late to have an effective contribution to the decarbonisation of the global economy to prevent global temperatures rising by more than 1.5°C above preindustrial times. Wind, solar, tidal, hydro, geothermal and traditional nuclear power, along with new technologies such as green hydrogen (if achievable at a competitive cost) and bioenergy carbon capture and storage (BECCS), as well as innovations that improve energy efficiency, are likely to remain the dominant growth areas as the world seeks to decarbonise to reach 2050 goals. In the very short term, they will offer little relief to higher fuel prices that are challenging some businesses and households, especially against a backdrop of a strong impulse to quickly cut reliance on fossil fuels.

Nevertheless, this dynamic is creating opportunities, especially for companies providing best-in-class technology for improving energy efficiency and network efficacy. Companies like AVEVA, which has market leading technology to improve the efficiency of industrial processes across a variety of sectors, including mining and energy, are in a sweet spot. Indeed, RELX and Ascential, both of which have data divisions that we believe are not fully understood by the market, also have a long runway of potential growth as a result of positive ESG momentum. Mears, Genuit, Weir, Centrica and Currys are all extremely well positioned to benefit over the medium to long term from the energy transition and sustainable trends.

A job for central banks

When it comes to greenflation, central banks, which in the UK and Europe (although not the US) have adopted policies to green their bond buying programmes, play a paradoxical role. Introducing a green bias to bond purchases can have a significant influence on the capital costs of energy companies on the one hand, but raise inflationary pressures on the other. At the best of times, energy inflation is difficult for central banks to contain, especially in the UK. The quote above from Professor Jonathan Haskel summarises the problems the Bank of England has in dealing with exogenous sources of inflation nicely: “…central banks cannot grow more food, supply more gas or make the wind blow stronger.”[iv]

Haskel’s point is that there is a limit to what the Bank of England can do to combat the role of supply-side or “outside” issues like food and energy shortages. He notes that in the years since the Bank of England became independent in 1997, some 62% of inflation has come from external sources. Given the dominant impulse has been deflationary, and the role of the central bank over the last decade has largely about stoking demand rather than curtailing it, it does give you pause for thought about the challenges ahead in a more inflationary environment.

However, there are some unique characteristics of the current inflationary spike which Haskel suggests are especially beyond the Bank’s ability to control: a lack of wind, which has influenced gas prices in the past year. Increasing interest rates might cushion the impact of rising global energy prices by lifting the value of the pound and therefore reducing the dollar cost of energy, but it can do little to address the causes of that inflation whether they be increased global demand from other countries or, indeed, due to issues associated with decarbonisation and the energy transition.

Nevertheless, where the Bank does have a role is in managing inflation expectations, especially when it comes to those that feed through to wage demands. And with real interest rates deeply in the red and prices rising faster than wages, the debate about whether inflation will be transitory has quickly morphed into questions about the “credibility” of central banks not just to control the yield curve, which they have become quite adept at since the GFC, but to avoid a wage spiral, where the public respond to negative real wage increases with demands for more pay. This requires a particular marriage of art and science, especially as policy changes can take months or indeed years to work through the economy yet can have an immediate impact on expectations.

It’s inflation Jim, but not as we know it

Few believe there will be a return to the hyperinflation of the 1970s, but it is possible that levels will remain above the 2% target rates of the Bank of England and the US Fed for considerable time to come. There are, of course, short, medium and longer term pressures on both sides of the supply and demand complex. An easing of supply chain bottlenecks, which should occur within the next 12 to 18 months (if not sooner) will alleviate some inflationary pressures, and the rebasing of inflation data will flatter the headline numbers later this year, although CPI rates are likely to rise further in the short-term. However, the energy transition and the widespread shift to stakeholder capitalism could continue to have inflationary consequences in the medium-term.

We don’t have a crystal ball when it comes to inflation and, given the incredibly complex nature of ESG trends, especially those surrounding the energy transition, it would be foolish to attempt to forecast the outcome to many of the trends mentioned above. Nevertheless, they remain key points of analysis and vital topics for engagement with investee companies and debate across our investment team. We are also paying particular attention to potential risks posed by a period of higher inflation on business operations, but also the market’s handling of what is a unique backdrop for many investors who have not experienced an inflationary environment first-hand. We could see some very interesting mispricing, which we would argue is already the case with the likes of AVEVA, mentioned above.

We don’t have hard restrictions on our portfolios, but actively engage with businesses across a range of ESG issues as part of our wider analysis of a company’s key material issues. For us, it makes sense to invest in mining companies, as long as they are behaving responsibly, and as long as we exercise all the rights that come with the role as shareholders on our clients’ behalf. We want businesses to be good neighbours and citizens.

Finally, we should state that climate change itself is inflationary and is already presenting cost pressures in terms of addressing food and water security, shoring up infrastructure and managing the risk to human health. While Greenflation may be a short-term challenge for policy makers and society; the alternative of not dealing with the climate emergency could be much worse.

Sources:

[i] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41578-021-00325-9

[ii] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41578-021-00325-9

[iii] https://theconversation.com/conservative-nuclear-fusion-by-2040-pledge-is-fantasy-their-record-on-climate-change-is-too-little-too-late-124404

[iv] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2021/november/inflation-now-and-then-speech-by-jona%20than-haskel.pdf?la=en&hash=C4908906B6735B600D288F7E8F3816BF09A9FE8C

Key Risks